Antenatal Diagnosis

Being told your baby has a problem with their heart is both frightening and emotional for parents and their families.

Here we hope to help you understand your baby’s heart problem and explain some of the choices you have been given. If at any time you would like to chat through the information you have been given, do not hesitate in giving the LHM team a ring on 0121 455 8982.

There are many different congenital heart defects (CHDs). A ‘congenital’ problem is one that a baby is born with. Some are minor defects such as small holes in the heart which may not need any treatment. Others, although more serious, can be corrected with an operation.

The third group are extremely serious conditions. Single ventricle heart conditions fall within this category. A series of surgical operations can be offered to allow a child a chance of life, but they will never be cured of their condition, and they will have to learn to live with different lifestyle restrictions and, as a result, have an uncertain future. Some conditions, for example, Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS), may have a more complex longer- term outcome than others.

The following information aims to help parents understand these extremely complex abnormalities of the heart and the implications they will have for their baby, and we explain the treatment pathways available to them.

It is important that you explore all the options available to you and your child and give each due consideration. Research the issue, find out what all the options are, talk to Little Hearts Matter, the doctors and nurses too. Give yourself time to come to a decision that you, as a parent, feel is the right one for your unborn child. After all, you will need to live with that decision whichever way you go. Remember, there is no right or wrong. Whatever the decision is, it is ‘ok’.

Contents

(Clicking the links below lets you jump to the different sections)

-

The diagnosis

-

Genetics

-

Who can help me understand this condition?

-

The choices

-

Continuing with the pregnancy with a view to offering surgery at birth

-

Ending the pregnancy (termination)

-

Comfort (palliative) care

-

Future pregnancies

-

What to expect when living with a baby or child who has half a working heart

-

Practical Tips

-

Ideas of questions to ask at your next hospital appointment

-

Antenatal Family Stories

-

Further sources of support

The Diagnosis

“I don’t really understand what’s wrong with my baby”

In order to understand what is wrong with your baby’s heart, it is important to have an understanding of how a normal heart works and how the heart works whilst the baby is still in the womb.

The normal heart

Understanding the normal flow of blood through the heart can be daunting so here we have described it in two ways.

The heart is a clever pump. Its job is to collect and send blood to different parts of the body. Blood contains all the things we need to make energy: oxygen, nutrients (food) and water, which it takes to every part of the body so that every part of the body has the energy it needs to work, grow and repair.

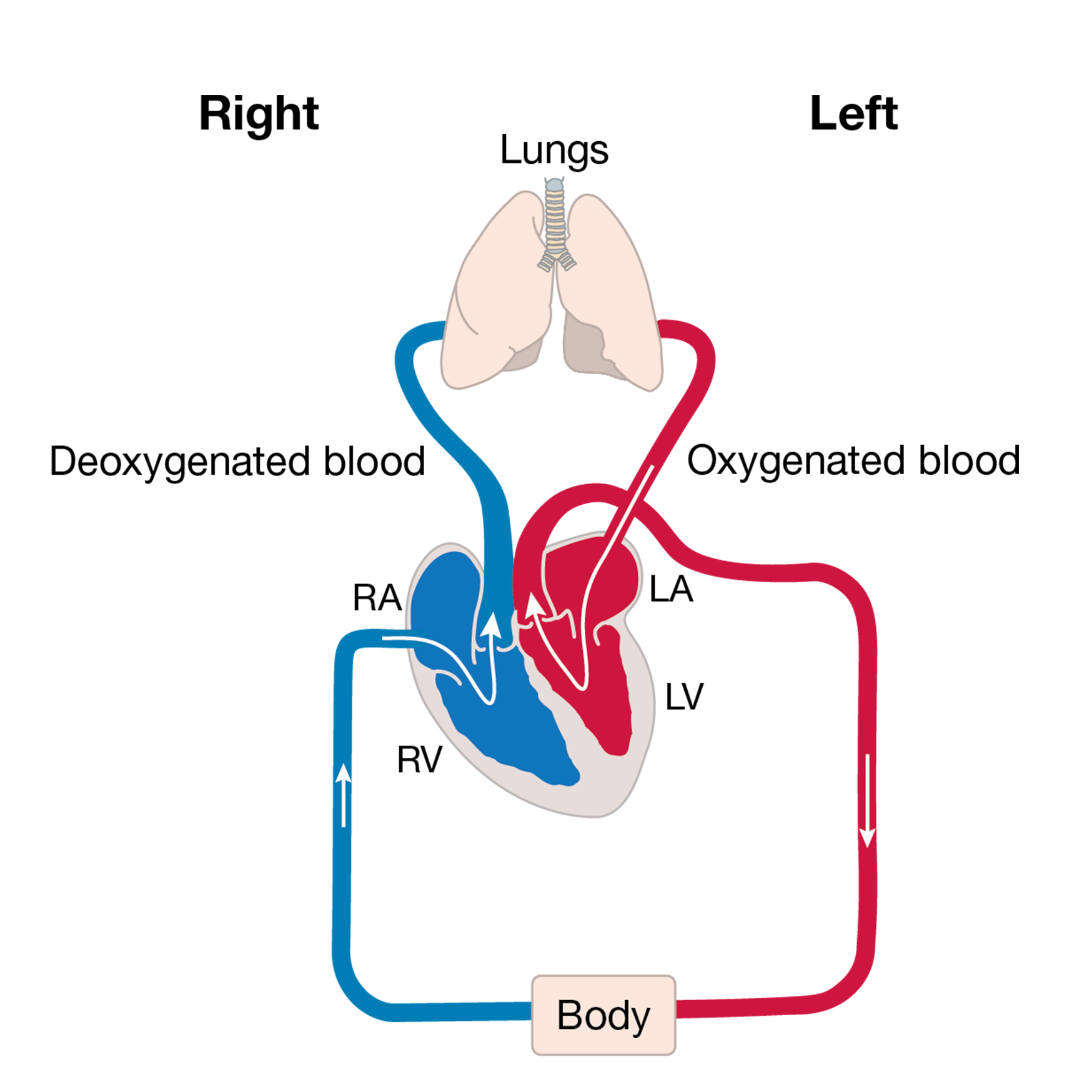

The body’s circulation has red blood that is filled with oxygen and blue blood that is empty of oxygen.

The heart has two sides. The right side’s job is to collect blue blood from the head, neck and body into the top right chamber (the right atrium). It then passes into the bottom chamber (the right ventricle) which pumps the blood to the lungs. The lungs do their job and pass oxygen into the blood; this turns the blood red. This oxygen-filled blood then needs to be pumped around the body by the heart. The red blood is collected in the top left chamber (the left atrium) and then passes to the lower chamber (the left ventricle) that pumps the blood out of the heart and around the body.

The body uses all the oxygen in the blood, turning the blood blue, and then sends it back to the right side of the heart to start the journey all over again.

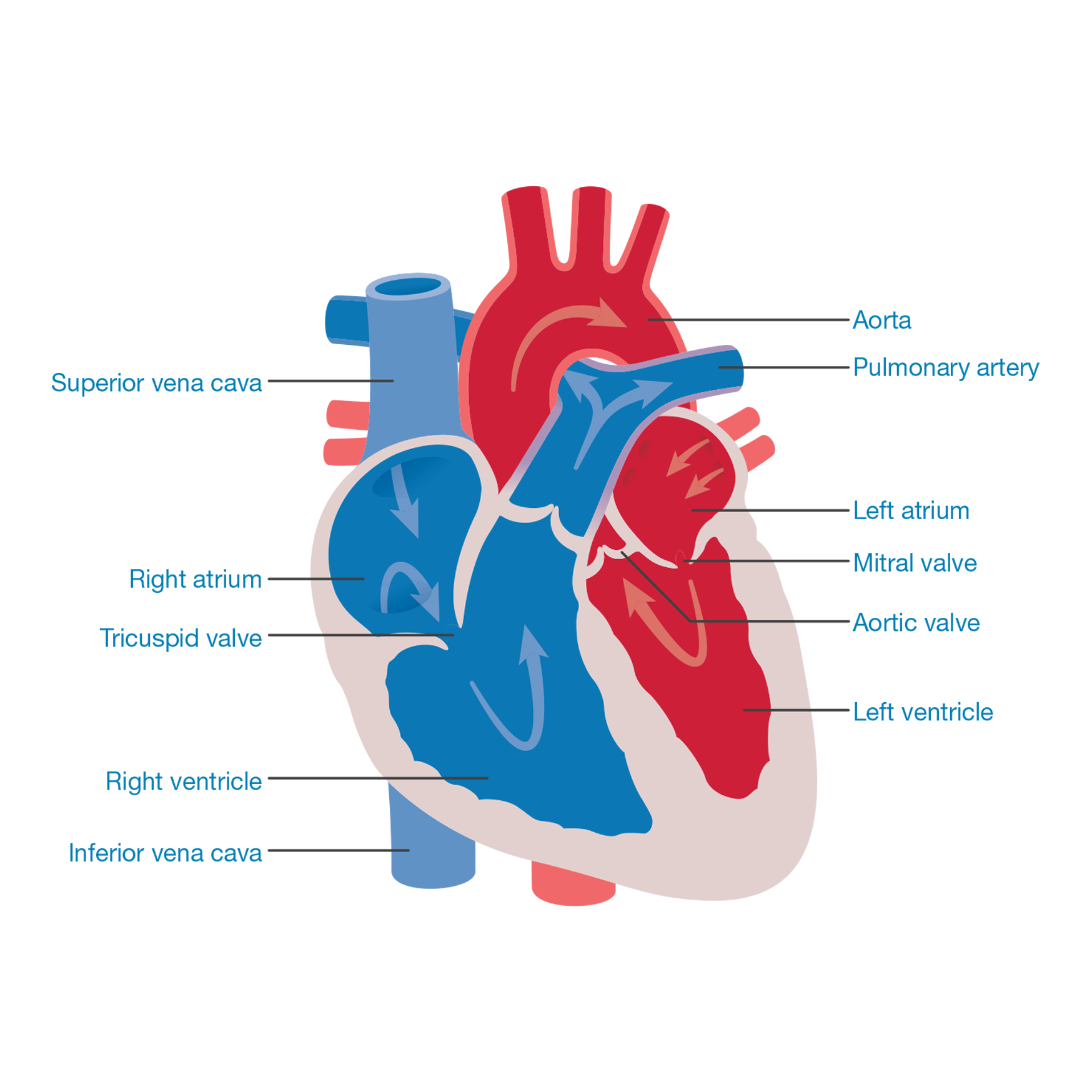

The following paragraphs explain the heart again but use more of the terms you may hear from your medical team and the picture looks more like a real heart.

This is how the journey begins: blood returns from the body, via the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, to the right side of the heart into a collecting chamber (right atrium). This blood has a bluish tinge (blue blood) because the body has taken (extracted) all the oxygen from it (deoxygenated blood).

The blood passes through a valve (tricuspid valve) into a pumping chamber (right ventricle), which then pumps the blood to the lungs via the lung arteries (pulmonary arteries).

As the blood passes through the lungs it picks up oxygen: this turns the blood a red colour (oxygenated blood). This blood flows to the left collecting chamber (left atrium) and then passes through a valve (mitral valve) to the left pumping chamber (left ventricle).

The left ventricle then pumps blood to the body through a valve (aortic valve) via the main body artery (aorta).

The body uses the oxygen from the blood to help make energy. As the oxygen is used up, the blood takes on a blue colour and needs to return to the lungs to collect more oxygen. The journey then starts again.

Click below to watch an animation about how the normal heart works.

The circulation before birth (fetal circulation)

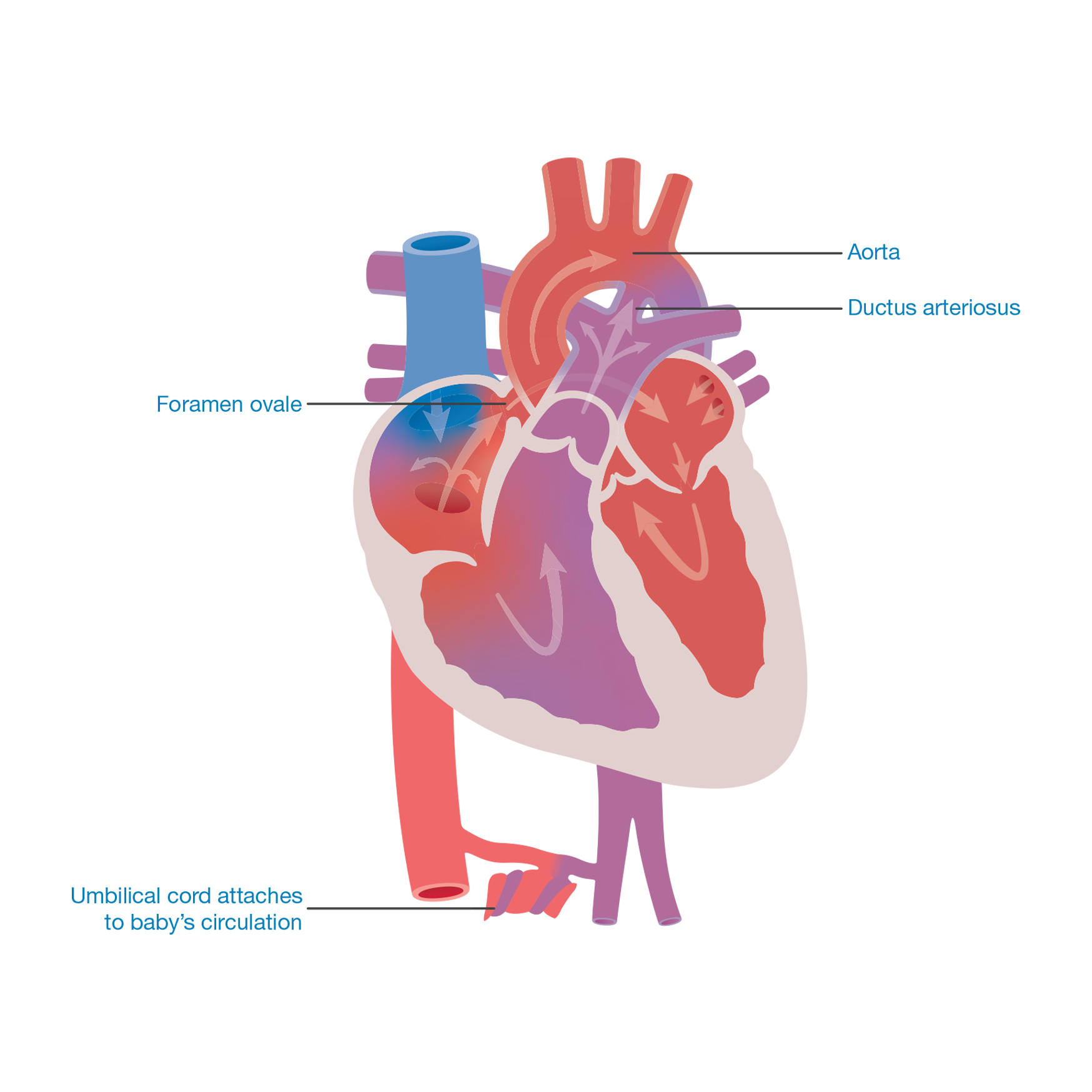

When the baby is still in the mother’s womb it does not need to breathe for itself as the mother is supplying all the oxygen to the baby via the umbilical cord.

The circulation before birth is different from that after birth. It is designed so that the oxygen-filled blood from the umbilical cord goes to the most important parts of the body, for example, the brain. Very little blood needs to go to the lungs.

The heart has designed a series of bypass systems. There is a hole between the upper collecting chambers (the left and right atria) called the foramen ovale. Some oxygen-filled blood passes from the right to the left collecting chamber then on into the left pumping chamber (left ventricle) which pumps the blood around the body. Some blood continues from the right collecting chamber down into the right pumping chamber where it is pumped up to the lungs, via the pulmonary artery.

The second bypass is a connection between the lung artery (pulmonary artery) and the body artery (aorta). The connection is called the ductus arteriosus (duct). Blood passes from the right pumping chamber (right ventricle) into the lung artery (pulmonary artery). Some of the blood travels through the lungs but most of it flows through the duct to the body artery (aorta) and around the body.

When the baby is born and starts to breathe for itself, the bypass systems are no longer needed. Gradually over the first few days or weeks after birth, the duct (ductus arteriosus) and the hole (foramen ovale) between the upper two pumping chambers will close off and the baby’s circulation will be as described by the heart condition diagnosis (as outlined in the following sections).

What exactly is wrong with my baby’s heart?

A detailed account of each specific heart abnormality (with diagrams) will be discussed with you by the fetal cardiac specialist. For more information, have a look at the section single ventricle heart conditions and their treatments where you will find diagrams, animations and a simple written description of the heart problem. Take the information to future appointments with your medical team, who can use it as a tool to help you gain a greater understanding of the heart problem.

The written information can be a reference point when you go home. It can also be very helpful when trying to explain the heart problem to family and friends.

Click here to read our updated information explaining single ventricle heart conditions and their treatments.

Why has my baby got something wrong with its heart?

The baby’s heart is being formed at around the fifth week of a pregnancy, just at the stage when you realise you are pregnant. In most cases it is impossible to give a specific reason for there being a heart defect. In the majority of cases the reason is not currently known.

However…

There are a number of factors which are known to increase the risk of having a baby with a heart problem, such as:

- A history of previous children, either parent or other family members having had a congenital heart problem (heart problem that the baby is born with).

- There may be a fault in the baby’s genetic make-up which has caused the heart defect (See genetics information further down).

- Diabetes in the mother, particularly if poorly controlled.

- Illegal drug abuse or serious alcoholism.

- Some medications such as those used for the treatment of epilepsy carry a small risk of causing heart problems, but are essential for the mother to keep her healthy and well.

- Other problems with the baby, for example, stomach or bowel problems.

Did we cause the baby’s problem?

Parents often worry that they are responsible in some way for the baby’s heart condition, but it is highly unlikely that there is anything you have done or not done which would have caused the problem.

Genetics

Many families who have a child with congenital heart disease ask why their child was born with the condition. In some cases the malformation will have occurred because of a genetic problem that has affected the heart as it formed in the womb.

A blueprint

When a new house is built, the architect draws up a plan of what the house will look like and how it is going to be built. When a new child is being created, information is drawn from the mother and the father to make a plan of how the child will look and how their body will be put together to work.

A genetic blueprint

Every person in the world has a genetic blueprint of their own. The blueprint is stored in every cell in their body and holds the information required to help the body grow, develop and work properly. The information is made up of lots of messages which we call genes. We have about 30,000 genes in each cell of our body. Different genes carry different messages that are responsible for instructing our body to do specific things. For instance, genes determine the colour of our hair or eyes or how cells work in different organs, for example, the liver, heart or lungs. The genetic blueprint is our very own information computer.

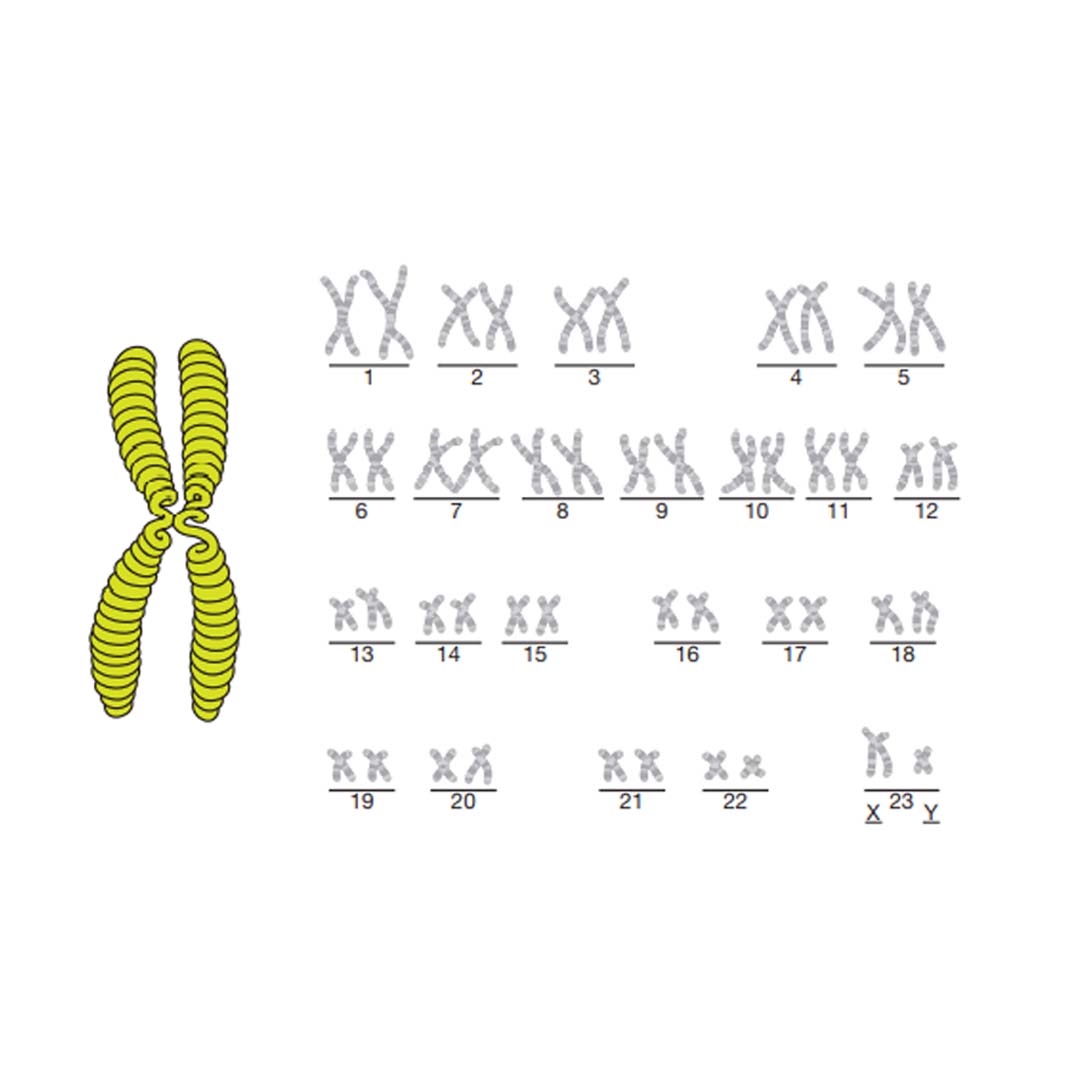

The genes are stored in coils and split into chromosomes (see the diagram on page 16). Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, so 46 in total. 23 chromosomes (one of each pair) come from the mother and the other 23 from the father. They are transferred in the egg and the sperm that make a child.

The picture on page 16 shows what the chromosomes look like – if you look at the last set of chromosomes in this picture you will see that they are labelled X and Y. These are the chromosomes that 16 decide if you are male or female. The chromosomes picture must represent a man because there is an X and a Y chromosome. A woman always has two X chromosomes. The sex of a baby is determined by which chromosome comes from the father: X for a girl, Y for a boy.

Genetics and heart disease

Some congenital heart conditions are linked to a genetic disorder such as Edwards’ syndrome or 22q Deletion. These disorders are caused when one of the 46 information chromosomes is malformed. As the baby grows in the womb, the genetic malformation will cause a particular part of the heart to develop incorrectly. In some cases the genetic condition can be detected before birth.

Geneticists (genetics doctors) are always looking for genetic causes for congenital conditions; however, there are many heart conditions that do not have a specific genetic cause. Many of the single ventricle heart conditions fall into this group.

There may be many factors, as yet unknown, that cause a baby’s heart to develop abnormally. The problems can occur early in pregnancy as the heart forms (before three months) or later as the heart grows.

Congenital heart conditions occur in 1 in 130 pregnancies.2 If you have previously had a child with a single ventricle heart condition the risk of it happening again rises to between 5 and 8%.3 There is also a risk to any pregnancies in the person with the condition and their brothers and sisters. Although the risk is higher, over 90% of future babies will have no problems with their heart.

What further tests will we need?

When any abnormality is found in a baby, it always raises the question whether it has been caused by a problem with the baby’s chromosomes (genetic make-up).

Many families who have a child with a congenital heart problem ask why their child was born with the condition. In some cases the malformation will have occurred because of a genetic problem that has affected the heart as it formed in the womb.

Tests available

There are currently three diagnostic tests available which look at the baby’s genetic make-up:

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

Taking a sample of the placenta. This is offered in early pregnancy, and would be relevant for expectant mothers with an increased nuchal translucency measurement (a measurement of a skin fold seen on the neck of the baby).

Amniocentesis

Taking a sample of fluid from around the baby.

Fetal blood sampling

Taking a sample of blood directly from the baby.

All of these tests carry a risk of miscarriage and it is therefore extremely important that parents are encouraged to think through the implications of what they would do with the additional information.

Talk to your midwife or obstetrican to see what would be the most appropriate test, if any, for you.

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

- This test is used in early pregnancy when an increased nuchal translucency measurement has been found.

- The miscarriage rate is 1%.

- A fine needle is guided, by scan, through the abdominal wall into the placenta where a small sample is removed.

- An initial result will be available within two to three days and looks for the three major chromosome abnormalities: Down’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome and Patau’s syndrome.

- The complete test results will take one to two weeks.

Amniocentesis

- This is the most commonly used diagnostic genetic test. It has a miscarriage rate of 1%.

- A fine needle is guided, by scan, through the abdominal wall into the uterus where a sample of fluid from around the baby is taken.

- The skin cells shed by the baby into the fluid are grown (cultured) and examined to give the chromosomes (genetic make-up) of the baby.

- An initial result will be available within two to three days which looks for the three major chromosome abnormalities: Down’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome and Patau’s syndrome.

- The complete test results will take two to three weeks.

Fetal blood sample

- This test has a miscarriage rate of 1%.

- A fine needle is guided, by scan, through the abdominal wall into the uterus where a sample of blood is taken from the umbilical cord or from a small blood vessel in the baby’s abdomen.

- Fetal blood sampling is less commonly used to test the baby’s genetic make-up, but sometimes your medical team may say it is their preferred test.

What is the advantage of having a test?

Every couple will need to think through the reason why they might choose to have a test. Some considerations are explored below.

Some parents feel that they need to know whether the heart problem in their baby is part of a genetic syndrome, such as Down’s syndrome, as this additional information may help them choose the way forward.

There are certain serious genetic conditions which may mean that the baby will not survive pregnancy or live for long after birth and parents may be advised that the option for surgery would not be in the baby’s best interest.

For some parents, knowing their baby has a genetic syndrome in addition to a major heart abnormality may help them with the difficult decision of whether or not to continue with the pregnancy or consider comfort care (palliative care) after birth.

Other parents choose to have a genetic test in order to obtain as complete a picture of their baby’s problems as possible, so that they can prepare themselves and their families during the remainder of the pregnancy.

Who can help me understand this condition?

You may have been initially alerted that there is a problem with your baby’s heart by a radiographer/sonographer carrying out a routine scan. Understandably they will not be able to give you a detailed diagnosis, but will refer you as quickly as possible to a specialist fetal cardiologist, who will be able to make a detailed assessment of your baby’s heart and discuss the problem with you.

You will probably be feeling very anxious and overwhelmed by the amount of complex and upsetting information you are trying to take in. You will be given written information about your baby’s heart condition to refer to and the contact numbers of specialist midwives in fetal medicine and/or specialist congenital cardiac nurses from the children’s cardiac unit.

The role of these specialists is explained below.

Specialist fetal cardiologist

This is a congenital heart doctor who specialises in the care and treatment of babies and children with heart conditions. They will give you the diagnosis and discuss at length the implications for your baby.

Fetal medicine consultant

This is a doctor who specialises in the care and treatment of pregnant women whose babies have some abnormality. They may also carry out a scan to check whether there are any additional problems in the baby and discuss with you whether you would like any further tests.

Obstetrician

This is a doctor who specialises in pregnancy and the birth of the baby. You may have an obstetrician close to your home who manages the day-to-day issues of pregnancy and an obstetrician who works as a fetal medicine expert at the regional specialist maternity unit.

Specialist midwives in fetal medicine

These specialist midwives are highly experienced in supporting parents through the many difficult decisions to be made following the diagnosis of an abnormality in their baby. They will be able to spend time with you going over the diagnosis, and may discuss the pros and cons of further tests and the choices available to you. They will give you written information and contact numbers for other sources of support.

Specialist sonographer

This member of the team works to scan the baby whilst still in the uterus. They report their findings to the specialist fetal team who will then offer more scans and screening.

Specialist congenital cardiac nurses

These nurses are usually based in the children’s hospital or unit where the heart treatment will take place. They are highly experienced in supporting parents whose children are having treatment for heart conditions and are a valuable source of information and support for parents whose unborn child has been diagnosed with a heart abnormality.

They have first-hand experience of the emotional strain parents experience when their children are having major surgery, They are able to explain the complex medical information to you in a simple and easy way and can advise you on how to cope with the practical issues of everyday life.

They will be happy to talk to you about any of these issues, together with with arranging a visit to the unit at some point prior to the birth if that is what you would like.

The choices

Having received the diagnosis and the results of any subsequent tests, the specialist medical team will explain the treatment options available.

In the case of a single ventricle disorder where there is no possibility of a cure, three treatment paths may be discussed.

- Continuing with the pregnancy with a view to offering surgery at birth.

- Ending the pregnancy (termination).

- Comfort (palliative) care.

Each treatment path is described in more detail below.

Continuing with the pregnancy with a view to offering surgery at birth

If you choose to continue with the pregnancy, there are many aspects of the birth and treatment of the baby to consider. The following information explores this area of care but it is very important to talk to your obstetric and cardiac team to clarify what care is planned for you and the baby.

What sort of surgery would the baby need?

The treatments available for each specific condition will be explained to you by the fetal and paediatric cardiac medical teams. A series of operations will be required soon after birth and in early childhood. These are described in more detail in the single ventricle heart conditions and their treatments section of the website.

If we decide that we would like surgery, who will carry out the operation?

There will be a team of cardiac (heart) surgeons at the specialist centre where the surgery will take place. They work closely with the cardiologists (heart doctors) and a team of children’s nurses who specialise in caring for babies and children who have heart abnormalities.

It is often possible during your pregnancy to arrange for you to visit the hospital where the surgery is planned. This can be extremely useful as it means that you will be familiar with the intensive care unit and the wards where your baby will be treated. You may also have an opportunity to meet with a paediatric cardiac surgeon to discuss the surgical procedure. Ask the team who have made your diagnosis for more information.

Will we have to travel to receive treatment?

As this type of surgery is very specialised, there are only a small number of children’s heart units in Great Britain that have teams with the expertise needed to carry these operations. It may be necessary to travel to ensure that you and your child receive the highest-quality treatment and care.

Following discharge after surgery it may be possible for ongoing medical care to take place in a hospital closer to home.

What are the risks of surgery?

It is important to remember that each and every child is unique and that although the medical team will be able to give expectant parents an idea of the national statistics and unit statistics for surgical success, they may quote a higher or lower risk for each individual child.

Can the baby have a heart transplant?

Heart transplantation is one of the possible treatments for single ventricle heart disease, but it is not offered as a first treatment within the United Kingdom for the following reasons.

- There are very few donor hearts small enough for a baby available in the United Kingdom.

- Transplanted hearts do not last for ever and there are many risks involved throughout the recipient’s life. Offering surgery as a first treatment path and retaining transplant as a future option offers a greater chance of a longer life for the child.

Where will I have the baby?

Your baby needs to be delivered in a hospital which has a neonatal (newborn baby) intensive care unit where a specialist team can carry out the immediate care that your baby will require after birth. This team will also organise the safe transfer of your baby to the children’s heart unit if this is the plan after birth.

If the hospital where you initially booked to have the baby is a small district hospital they may not have these facilities. It may therefore be necessary to transfer your obstetric care to a unit which has these specialist services.

When an abnormality is found in a baby, the focus of attention for you and the healthcare professionals shifts towards the baby. It is very important that the needs of the mother are not forgotten. All the normal antenatal check-ups should proceed as planned with your midwife or your GP or at the hospital.

There may be extra scans arranged at the specialist unit to monitor the baby’s condition and often parents find these consultations and the time leading up to them stressful, as they wonder if further problems may be detected. You may find that the specialist midwife or the specialist cardiac nurse are an invaluable source of support and can help you with the ongoing concerns you have about the pregnancy and birth (make sure you take the number of the specialist nurse with you at the end of any appointments). They will also be able to liaise between the cardiac team from the heart unit, your own hospital, your GP and community midwife to ensure that all carers are kept up-to-date with information and the baby’s condition.

Preparing for the birth

Many parents feel increasingly anxious as they approach the time of birth. Mothers often express how they feel protective of their unborn baby, knowing he or she is safe inside them. Facing the reality of what their baby will go through after birth is a daunting prospect over which they have little control.

The obstetric team will put you in touch with the specialist cardiac nurse at the hospital where your baby will receive their treatment. They will arrange for you to visit the children’s hospital and speak to the team who may look after your baby once they are born.

Once again, being able to talk through these feelings with your midwife, GP, obstetrician or cardiac specialist nurse can be helpful.

How will I tell the baby’s brothers or sisters about their heart condition?

It is important that all of the children in the family have an idea that their baby may have a problem with their heart so that they are not surprised if the baby stays in hospital after birth. They may well be picking up your upset around the diagnosis and hearing that you are worried about the baby. Don’t try to hide all your feelings from your other children.

The most helpful advice when telling siblings about a sick baby is to be guided by their questions, and to answer them in as honest and non-frightening ways as possible. ‘Talking to Children’ is a helpful book that can help guide the conversation, visit www.arc-uk.org/for-parents/publications-2/talking-to-children-2

Will I need a Caesarean section?

Many parents, understandably, think that because the baby has a heart problem, a Caesarean section would be the safest way to give birth to the baby.

In fact, for most mothers, the opposite is true for the following reasons:

Whilst the baby is in the womb, it is receiving all the oxygen it needs from the mother via the placenta (afterbirth) and this continues throughout labour until the baby is born and the umbilical cord is cut.

Being born naturally allows the baby’s chest to be squeezed as it comes through the birth canal. As the baby is born the release of pressure on the chest encourages the baby to take a deep breath and this helps the lungs to expand.

Mothers understandably want to spend as much time as possible with their baby in the time leading up to the first operation. Their recovery following a normal vaginal birth will be much quicker than following a Caesarean section.

During labour the baby’s heartbeat will be monitored. If there are any signs of distress, or if there are problems for the mother, a Caesarean section may become necessary.

Some mothers may require a Caesarean because of problems that they have had with a previous birth or because of a problem with the size of their pelvis or birth canal. If this becomes necessary the maternity hospital will link with the cardiac team to ensure that the mother has as much contact with the baby as possible.

The most important thing to remember is that the mother and baby are kept as well as possible.

Will I need to be induced?

It is preferable for your baby to be born at the end of pregnancy, when it is well grown and the lungs are mature, and you go into labour naturally.

Prior to 34 weeks of pregnancy, the baby’s size in combination with immature lungs may mean that surgery is not possible.

However, it may be necessary to induce labour for the following reasons:

- If you have gone past the date when you expect to have your baby.

- If your blood pressure rises and it is felt that it is safer for the baby to be delivered.

- If the baby stops growing.

If you are giving birth to your baby at a unit which is some distance from where you live, it may be easier to plan a date for induction of labour after the 38th week of pregnancy.

This can be planned in liaison with the neonatal unit and the specialist cardiac unit to ensure cots are available.

Can my partner be with me when I have the baby?

As with all normal deliveries your birthing partner can be with you in the delivery room. In most cases this would be your partner, a member of your family or a good friend.

If you need a Caesarean section and you are awake for the delivery your birthing partner can be with you so that you can share the birth of your baby. If the Caesarean section is an emergency, or you chose to be asleep for the procedure, your birthing partner can be close by in the recovery room. Once the baby has been born safely they will be able to hold the baby whilst the procedure is completed.

In all cases the baby will be seen by a neonatologist (baby doctor) first to make sure that they are stable. If the doctor is happy with the baby’s condition you will be able to hold the baby.

Will I see the baby after he or she is born?

The baby should be in good condition at birth as the connection (ductus arteriosus) between the lung artery (pulmonary artery) and the body artery (aorta) does not close immediately. A neonatologist (baby doctor) will be on hand at birth to assess the baby’s condition.

If the baby is stable, there should be no reason why you should not be able to hold and cuddle your baby and put the baby to the breast if that is your wish.

After a short while, the neonatologists will want to take the baby to the neonatal unit to insert a drip (infusion). In the case of babies dependent on the fetal circulation, this enables the neonatologists to give the hormone Prostaglandin, which keeps the ductus arteriosus open and aims to keep the baby stable until they receive their first surgical treatment.

Who will be looking after the baby?

The neonatologist and nurses in the neonatal unit will be caring for your baby and working to keep the baby’s condition stable. A scan of the baby’s heart will be carried out when the baby reaches the heart unit. On the basis of the assessment, surgery can be arranged and at every stage the doctors will discuss the plan of care for the baby with you.

Your partner and immediate family – other children and grandparents – can visit the baby on the neonatal unit and depending on how you feel after the birth, you will be able to spend as much time as possible with the baby. Do check your hospital’s visiting policy.

If the baby has to be transferred to a specialist heart unit, can we go with him or her?

You will be encouraged to go to the children’s heart unit with your baby, although the baby will travel by ambulance with medical staff if the heart unit is in a different hospital.

If you are well enough to be discharged you may follow the baby in your own car or the hospital will arrange transport if you are still a patient.

The children’s hospital will find accommodation for both parents so that they can stay near to the baby. They often also have space to accommodate siblings who may like to visit through treatment.

Will I be able to breastfeed the baby?

Once the newborn baby’s condition has been assessed and if they are found to be stable it may be possible to put the baby to the breast soon after delivery. Once the drip has been inserted and the baby is receiving Prostaglandin to keep the duct open, it may be possible to try different feeding methods.

Although breastfeeding will be encouraged, it is important to understand that feeding will be very tiring for the baby. To help support their heart function, they will need to have more calories than other babies, but they often do not have enough energy to take all the milk that they need. A mixture of feeding styles may be needed. For example, bottle or breastfeeding, calorie additives/special high-calorie milks and nasogastric feeding will ensure that the baby receives enough calories to grow.

If you are keen to breastfeed, ask for support from the hospital team and your visiting midwife. It may also help to talk to other parents who have successfully breastfed a baby with complex heart disease. This can be done through the hospital or through Little Hearts Matter. Even if breastfeeding is not possible, there may still be an opportunity to express breast milk. The dietitians can add extra calories and the milk can be given by a bottle or nasogastric tube.

Mothers of babies with complex heart complex heart conditions should never worry if breastfeeding is not possible. It is tough to feed by breast and the stress of all the hospital treatment and worry about the baby can create problems with milk production for the mother.

Who looks after the mother after the birth?

It is important that after the birth the mother’s medical needs are not forgotten in the midst of all the care being organised for the baby. Before the mother can be discharged from the maternity unit she will be examined by one of the obstetric team at the maternity unit. She will then be transferred to the care of either her home-based community midwife or the community midwife who covers the children’s cardiac unit. A new mother needs regular check-ups from the midwife. If there are any concerns about her condition whilst at the children’s unit, a midwife will be called and any hospital care will be organised at the closest maternity unit.

Although the mother is worrying about the baby, she must organise plenty of rest for herself and eat regularly. She needs to recover well from the delivery so that she has the energy to look after the baby once they are discharged home.

Ending the pregnancy (termination)

For some parents the knowledge that even following repeated surgery their child’s heart and lifestyle will never be normal, means that they choose to end the pregnancy before the baby is full-term: a termination. As well as speaking to the Little Hearts Matter team it may be helpful to seek other specialist advice. For more details see Further support section.

What would termination involve at this stage of pregnancy?

As most diagnoses of complex heart disease are made after the twentieth week of the pregnancy it is important to think about the method of termination that would be needed.

At this stage of pregnancy the only way for the pregnancy to be terminated is to give birth to the baby. Labour will be induced and the baby will be delivered vaginally. It is a difficult prospect to imagine going through a labour and parents often ask why the baby can’t be born by Caesarean section. There are risks to the mother associated with Caesarean section and so it is felt that the safest way to deliver the baby is to have labour induced with all methods of pain relief being available. Usually the baby will be born within six to eight hours. After 22 weeks gestation, ending the pregnancy often involves an additional procedure where the baby is given an injection into the heart prior to inducing labour to make sure the baby does not survive and suffer.

Your obstetrician will discuss specific details about your individual circumstances with you.

What will happen to my baby at birth?

Most parents feel apprehensive about the birth and the midwives caring for you will talk to you about your concerns. You will be given a choice as to whether to see and hold your baby as this is a very individual decision.

Many parents have found that seeing and holding the baby enables them to have very precious and real memories of the baby, and this has helped them in coming to terms with their loss. Most hospitals will take photographs and make a remembrance folder of the baby. Copies will be kept in your hospital file if you do not wish to see the baby at birth. Some parents choose to take photographs of their baby with their own camera.

What happens to our baby after we leave hospital?

Following the birth you will be visited by a member of staff responsible for bereavement services and they will discuss with you what your individual wishes are regarding funeral arrangements. The hospital will do its best to accommodate any religious or cultural beliefs the parents wish to be observed. It will be your individual choice as to whether you wish your baby to be buried or cremated. Hospitals can make all the necessary arrangements for the baby to be cremated or buried, however some parents prefer to make their own private arrangements for a funeral. This member of staff responsible for bereavement services will also inform you of the legal requirements surrounding registering the baby.

Following the birth you will be asked whether you would wish your baby to have a post-mortem. It is another very difficult decision for bereaved parents to face, but it can give additional information that might answer some of your questions which otherwise would not be known.

Will this happen to us again?

Following a termination, the question uppermost in parents’ minds is: “will this happen again in a future pregnancy?”. To answer this accurately a number of essential pieces of information are required and a post-mortem may be the only way to complete the jigsaw.

If a heart condition has been detected in a previous pregnancy there is an increased risk that it may occur again. The obstetric team will offer specialist scans for future pregnancies.

If the medical team feel that the risks of a recurrence are high because of a strong family history or other abnormalities they may refer a family for special genetic counselling, See Future Pregnancies section.

If I terminate the pregnancy can I have other children?

Terminating your pregnancy because of an abnormality will be a physically and emotionally traumatic experience for you and your partner. However, it should not mean that you cannot have other children.

There are few physcial risks associated with termination and women usually recover relatively quickly.

The emotional effects of termination vary for each individual family and you need to grieve for your baby in your own way and time and this may affect your decision of whether or when to try for another baby.

Palliative Care

Some parents feel that they could never contemplate ending a pregnancy, but do not feel that they want their baby to go down the surgical route of treatment. In these cases, ‘comfort care’ for the baby can be offered. This may be explained as ‘letting nature take its course’. This may be an option in some cases and will be discussed below.

What happens to the baby if we don’t want surgery?

If you have decided that you do not wish your baby to have surgery, it is very important that you have time to care for your baby for the short period of their life. You will be given as much support as possible to enable this to happen either from the hospital team of specialist baby doctors (paediatricians/neonatologists) and the team of nurses on the neonatal unit or from the local hospice team. These doctors and nurses are skilled in providing tender loving care for babies to keep them comfortable and in supporting parents through this difficult time.

Some families choose to go to a children’s hospice or home during this difficult time where considerable support can be provided in a more relaxing environment.

Your fetal cardiology team can give you more information about the different types of support available where you live.

If I choose comfort care as my treatment choice what sort of birth will I have?

The birth can be the same as for any other baby. The obstetrician and midwifery team caring for you during your pregnancy will discuss your wishes with you prior to giving birth. There need be very little monitoring and in most cases, a Caesarean section would not be necessary unless the mother showed signs of physical distress.

It would still be very important that the mother and father feel involved with the birth and that they have the opportunity to make the birth as memorable as they wish.

Caring for your baby

After the birth of a terminally ill baby, families have a choice about where they spend time with their child until they die. Some choose to stay in the hospital; others choose to take the baby to a local children’s hospice. Some parents choose to take the baby home.

Most parents are concerned that their baby might suffer or be in pain. The doctors and nurses will ensure that the baby is kept comfortable and will support you in giving whatever care is necessary for the baby.

Friends, relatives and other children would be able to visit freely.

During this time parents would be encouraged to build memories of the baby through the taking of photos and the collecting of mementos.

Representatives of religious faiths can visit and services can be held at the hospital.

The main aim of this special time is to allow families to be as involved with their child as they would like, whilst ensuring that the baby is comfortable. The hospital or hospice bereavement team will be at hand to offer help and support both before the baby’s death and in the days after.

Who will help us if we want to take the baby home?

Some parents will want to care for their baby at home. They will be supported by the community neonatal nurses in liaison with the doctors from the neonatal unit.

In some areas of the country there are specialist teams of doctors and nurses, sometimes linked to a children’s hospice, who support parents who wish their baby or child to die at home. The maternity and neonatal staff where your baby will be born will be able to give you information about how care is provided in your local area.

Parents who have chosen to do this have felt that it has given them the opportunity to look after their baby in the more relaxed environment of their own home. Some children can survive for many months and – rarely – years without surgery.

Following the baby’s death, parents will be given the opportunity to discuss their wishes about funeral arrangements with their local funeral director and any religious groups that they are involved with.

How long will our baby live?

Each family will be given a slightly different answer to this question.

Some babies depend on the circulation that they have inside the womb to keep them alive. As this circulation changes after birth (see Fetal circulation), their hearts will no longer be able to supply their body with oxygen and they will die, usually within the first week.

Other children born with only one ventricle will be able to live for longer. The implications of their type of heart defect will slowly affect them. Some children can survive for many months, occasionally for years. Due to the changes that happen in the lung arteries, surgery is not usually possible after the first few weeks of life.

Your medical team will be able to offer you more information about what would happen to your child if you choose this treatment path.

Future pregnancies

What are the risks of having another child with the same problem?

In any pregnancy there is a 1% chance of a baby having a heart problem. If you have had a previous child with a heart abnormality, the risk of a further child having a heart problem is approximately 2-5%. This is known as the recurrence rate.

There is a wide spectrum of heart abnormalities from relatively minor holes in the heart, to the extremely complex problem your baby has. The 2-5% risk encompasses the whole spectrum of heart abnormalities.

Remember the risks are still small. 95-98% of parents will have further children with completely normal hearts.

When planning a future pregnancy it may be useful to discuss your risks and ways for you to stay healthy with your GP, obstetrician or special midwife. This is known as prenatal care (care before the baby is conceived).

Will we be able to have any extra scans to reassure us?

Understandably, you will be very anxious that the condition may be present in a future pregnancy. Currently there are no blood tests available to indicate a heart problem. The first time that a problem could be detected is between 14 and 20 weeks. Your local obstetrician should arrange for a specialist cardiac scan with the local fetal cardiac team. This may seem a long way into the pregnancy, but the baby’s heart needs to be a reasonable size to be able to see all of the heart’s chambers, valves and main blood vessels. At 20 weeks the heart is approximately the size of a small walnut.

Further tests will be offered in early pregnancy to look for other conditions like Down’s syndrome and other organ abnormalities.

What to expect when living with a baby or child who has half a working heart

When you are first told that your baby has a heart problem it is very difficult to know what sort of life your child will lead. This section hopes to answer some of the most commonly asked questions about life at home.

It is extremely important to remember that each child is different and that not all of the information below will necessarily apply to your child.

Appearance

Children with heart disease look very normal. They may have a slightly blue tinge around the lips and fingernails (cyanosis). This is because they have a reduced amount of oxygen flowing around their bodies. After the final operation when the blue (deoxygenated) blood and the red (oxygenated) blood have been separated, they should be pink.

Development

A child with a single ventricle heart is likely to develop in the same way as other children of their age but they may meet their developmental milestones, the tests done by health visitors in early childhood, at the upper end of the normal range rather than the lower end. Children who recover well after surgery will normally be able to crawl, walk and run as other children of their age will do, although they may tire easily when they exercise.

They should go to mainstream school and be able to take part in normal learning but they may find concentrating for long periods difficult and the physical part of school life challenging because they lack the same energy levels as their peers. Socially the children will be able to develop normal friendships and take part in normal family life.

Some children need extra support in school to help them reach their full educational potential. Recent research shows that children with single ventricle heart conditions are more likely to develop educational or behavioural problems, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Asperger’s or Autism. This probably relates to the repeated surgery and low oxygen levels they experience in their early life.

Diet and growth

Children with heart disease need more calories than other children. Their hearts need more energy to function so they need to take in extra calories if they want to grow. The difficulty is that they do not have the energy to take the added calories that they need. For some small babies completing a feed is like running a marathon.

During the first few months of life, babies will need regular weight checks to ensure that they are growing and that they are gaining the calories that they need.

If they are not gaining weight then more calories will be added to their milk. If they are tiring easily whilst feeding (visit, single ventricle heart conditions and their treatments, heart failure), it may be necessary to rest them temporarily by feeding them down a tube that has been passed into their stomach. This could be either a nasogastric or PEG tube.

Most babies with a single ventricle heart need some sort of help to gain weight. Parents at home find feeding their greatest challenge as it takes a great deal of time and patience to help their baby gain weight.

Once Stage Two has been successfully completed, feeding often becomes less of a challenge. The babies gain more energy from the operation and they are often old enough to wean. It is easier to achieve weight gain when a child is eating solids.

Keeping a baby safe at home

When a baby goes home from the hospital after their first stage of treatment they often require monitoring to ensure that they are well. Parents will be taught what signs to watch for and who to contact if their child shows signs of being unwell.

Some babies are sent home with oxygen monitoring kits and scales so that a daily record of their condition can be taken and passed on to the hospital team.

Time in the hospital

The first stages of treatment are often complex and it can take a child time to recover. The aim will always be to get them home if they are well but it is important to be aware that a baby or child undergoing hospital treatment may be in hospital for long periods of time.

Activity

Most children with complex single ventricle disorders can walk and run. With support they should be able to ride a bicycle and play football in the back garden, but they will not have the energy to be able to play a full game of football or run in a competitive race as they grow older and they start to compete with their friends. Contact sports are not possible because of surgical scarring and anticoagulation treatment.

Long-term treatment

If the surgery offered, normally over three stages, has been successful, the children should not need to spend a great deal of time in hospital. They will need to have regular outpatient check-ups to monitor their progress, with the occasional short hospital admissions for tests.

Most children are on some of the medications described in the section Medications, but these are given at home and the children become used to having them.

Teenage and young adult life

As the children grow through their teenage years and make the transition into adulthood they often require a full review of their treatment. Their hearts grow as their bodies grow, creating an added strain on their heart’s ability to function well. This often requires cardiac interventions or changes in medication to balance the circulation.

It has become clear that adults with a Fontan circulation (the circulation created for a child with a single ventricle heart) often develop symptoms in early to mid-adulthood which affect their day-to-day life. These include breathing difficulties, heart rhythm problems, increased tiredness and a reduced ability to exercise. All will be on life-long medications.

Sadly, a half a heart will one day fail to work, eventually becoming untreatable. Some teenagers and adults may be referred for transplant assessment.

Little Hearts Matter has a number of information booklets that provide in-depth support and information on specific aspects of life with a single ventricle heart condition

Practical Tips

The following information is designed to give some practical hints and tips for parents expecting a baby with a single ventricle heart condition – parents often ask if there’s anything different they should buy, or indeed if they should buy things for their baby.

Whether to buy things for your baby is of course a personal decision, however the information below is based on the experience of a number of Little Hearts Matter’s families, and may help you to plan.

Clothes

- Some parents like to buy clothes as part of preparing for their baby’s arrival. Ideally they should be named to avoid being lost in hospital. For the time in hospital, front-opening, machine-washable garments are vital.

- It is usually a warm environment so the baby is unlikely to need lots of layers.

- Small sized baby-gros which open up completely to be flat on the cot (i.e. they have poppers down the front and down the inside leg) and have no feet in them are the most appropriate – these can then be worn if your baby is allowed to wear clothes in intensive care. Babies often have lines or monitoring equipment on their hands and feet, so these are the easiest to change.

- Front-opening vests are also useful in intensive care and on the ward as babies are checked frequently by medical staff.

- Some babies are stable enough to wait a couple of days for their surgery, in which case, you may want to dress them in their own clothes.

- Bootees or socks (if kept on!) can help your baby’s feet keep warm so that the sats monitor (monitor measuring oxygen levels in the blood) hopefully gives a better reading. Socks in a larger size might be useful to fit over the probes.

- A baby towel may be nice to have for the special first bath moment.

- A good supply of easily removable bibs (velcro not ties) is really handy so that any vomiting after feeds can be cleaned up more easily without having to completely change the baby.

- Scratch mitts are useful for some babies both to stop them scratching themselves and to stop them from pulling out tubes e.g. feeding tube. If scratch mitts are too big, try very small socks – they sometimes stay on better.

- Find out the hospital policy regarding nappies – many hospitals don’t provide them, and the last thing you want is to have to go out shopping for nappies instead of spending time with your baby.

- Many families bring a baby blanket to make the cot feel more homely. One of our members made a crochet blanket for her baby during her pregnancy – helping to keep busy and doing something positive for her baby. Another member suggested sleeping with the baby blanket before the birth to give baby something with mum’s scent on.

Equipment and toys

- Dummies are often recommended to help babies who are currently unable to feed to remember the sucking action. They may also help to soothe your baby.

- You may need to provide your own cold water steriliser, or simply a tupperware container with Milton or equivalent tablets.

- Some parents bring baby lotion.

- There is usually no need to take bottles as the hospital will provide the right kind of feed and teat if relevant.

- Some families like to bring music or stories for the baby to listen to.

- A musical toy to put in the cot is a nice touch.

- Some soft toys for the baby to look at also give the nurses something to prop the oxygen on!

For you!

- A camera (though you may need to get permission from the hospital before you start taking photos).

- Plenty of your own creams and lotions as the hospital environment can be hot and dry, and you will be washing your hands and putting on alcohol gel very frequently, which dries out your skin.

- Comfortable clothes and a pillow.

- A diary or journal for noting down what happens each day or how you feel.

For siblings

- Loads and loads of colouring books, crayons, activity books, puzzles, hand-held games, small scale play toys, etc.

- Their own comforters e.g.cuddly toys or blankets.

- A present from the baby.

- A doctor’s set so the sibling can be included in hospital play.

For going home

- A baby car seat is essential for when you are discharged.

- A cold water steriliser (using Milton tablets or equivalent) can be very useful for sterilising medicine syringes and tube feeding equipment. Not all babies need the feeding equipment, but most will need medicine syringes. Steam/microwave sterilisers should not be used for syringes or tube feeding equipment.

- Most parents buy a baby monitor so that they can listen out for their baby when they are not in the same room. Some parents also buy a movement monitor (apnoea mat) which alarms if the baby stops moving for a few seconds. The hospital will advise whether your baby has to have one, but even if the healthcare professionals don’t recommend it, some parents still use one for their own peace of mind.

- A bouncy chair can be helpful for feeds if you go home with tube feeding equipment, but you could also use the car seat for this.

Ideas of questions to ask at your next hospital appointment

About the diagnosis

- I don’t really understand what is wrong with the baby?

- Why has the baby got something wrong with its heart?

- Did we cause the baby’s problem?

- What further tests will we need?

- What treatments are available to help the baby?

- Who can help me understand the condition?

Treatment choices

- Am I allowed to terminate this late in pregnancy?

- What will termination mean for me?

- If I terminate the pregnancy can I have other children?

- What happens to the baby if we don’t want surgery?

- Who will help us if we take the baby home?

- If we have surgery who will do it?

- Will we have to travel to receive treatment?

- What are the risks of surgery?

- How long will our baby live?

The plan for the baby

- What will happen to the baby after it’s born?

- Who will be looking after the baby?

- Can we be with the baby?

- Will we be told what is happening with the baby?

- If the baby has to travel can we go with them?

- How will the baby’s condition be kept stable before surgery?

- Will I be able to breastfeed the baby?

- Can the baby have a heart transplant?

The future

- Can I have more children?

- What are the risks of having another child with the same problem?

- How will the baby be after surgery?

- What sort of life do children with this condition have?

- Do children spend their lives in a wheelchair?

Delivering the baby

- Will I need a Caesarean section? Will I be induced?

- Can my partner be with me when I have the baby?

- Where will I have the baby?

- Will I see the baby after it’s born?

Antenatal Family Stories

Click here to read our Antenatal family stories.

Further sources of support

Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC)

A charity which offers non-directive information and support to parents before, during and after antenatal screening; when they are told their baby has an anomaly; when they are making difficult decisions and continuing with or ending a pregnancy, and when they are coping with complex and painful issues after making a decision, including bereavement. ARC offers a telephone helpline, an online parent forum and a series of publications, for which you may incur a small charge.

Twins Trust

Is the UK’s leading twins and triplets charity. They offer support, information and courses.

National Childbirth Trust (NCT)

A charity which offers information and support in pregnancy, birth and early parenthood.